Feller's Master Stroke

(Or the elimination of an immovable object with another sharp object)

(picture credit: copy of Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master Stroke)

And so Alice bought herself an axe. She had scoured thousands of yard sales, hundreds of antique malls, scores of estate auctions, dozens of hoarders’ barns, scads of thrift stores, untold second-hand shops, and more than a few storage units, but this tumble down outbuilding smelled like a Pict’s bury: hoary, earthy, and just a bit foosty.

Alice closed her professional eye that relied on five senses and reached out with gut instinct. Something tapped her psychic shoulder. The feeling eldritch, but not arcane; the touch sacrosanct, but not occult.

Alice opened her eyes.

Standing tall on its head against a metal oil barrel, an axe rested. Power curled around it like a sleeping dog with a hermetic collar clutching secrets as a solitary oyster. The dark greasy stains on the wood and the oxide patina on the forged metal spoke of auld days.

“What’s that?” Alice asked her host, a graying man so tall that he had to stoop over once inside the outbuilding.

The graying man put his hands upside down on his kidneys. “You’ve got a good eye. That’s practically a family heirloom.”

“Would you be willing to part with it?” Alice proffered.

The man nodded. “I might. You’re here to buy. And I’m here to sell.”

“Before we talk price, let’s talk provenance,” Alice said.

“Alrightie,” the man said and reached down with a lean arm to pick the axe up by its handle. The axe being four feet long and the man well over six feet tall made Alice wonder if he couldn’t swing it and cleave her in two without a busting a sweat.

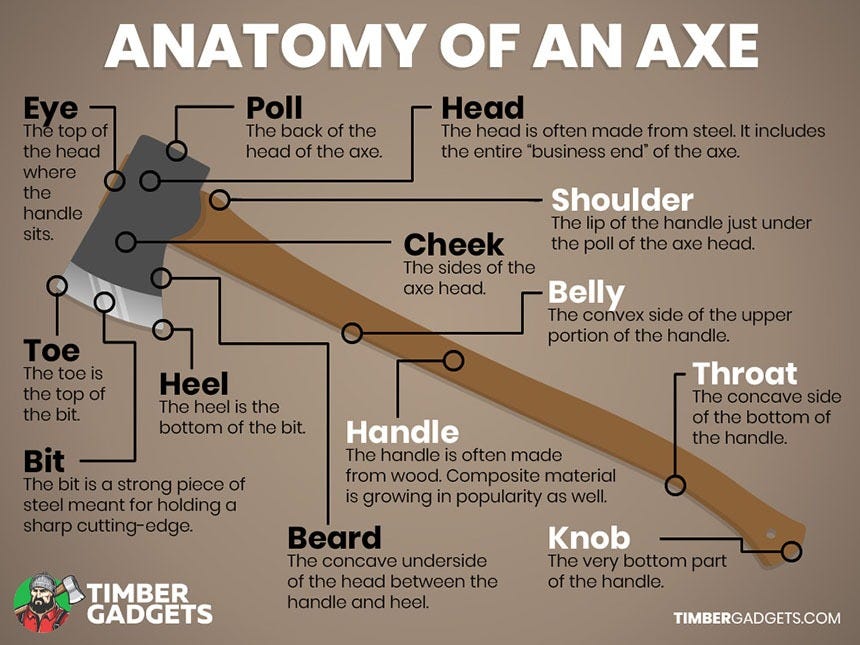

(photo credit: Timber Gadgets, in case you didn’t notice)

The man spoke: “We think it was made in the oldest woods beyond the oldest mountains in Europe, so it’s a true pioneer. A good ax stands like a man. This here top part is the ‘business end’ of the axe. The wedge is called the ‘head.’ The flat of it is called the ‘poll’ or the ‘butt.’ The flange part on either side of the handle is the ‘check.’ Where the handle pokes out of the head is the ‘eye.’

“The sharp end of the wedge is called the ‘bit.’ And the top is called the ‘toe’ and the bottom the ‘heel.’ The part of the wedge under the ‘heel’ and the ‘butt’ is called the ‘beard.’ Obviously, the stick poking out the eye down to the end called the ‘knob’ is the handle. But the upper end of the handle is called the ‘belly’ and the lower end is called the ‘throat.’”

The axe whispered into Alice’s ear that it was its own person. “How long has it been with your family?” she asked.

The man shrugged. “It’s been with my family ever since we’ve been in this country and that’s been about three hundred years.”

Alice nodded. “Bet you have some wicked family stories.”

The man looked to one side and pursed his lips. “It ain’t my family that’s wicked. It’s this here ax. My dad used it while he logged up to the day he died. And ‘fore that, my grandpa used it his whole life ‘fore he died and give it to my dad.”

“So, why part with it now?” Alice asked.

“Oh, I used it a good while myself until I had one job that went…well…queer and I mean the word in the way my Scotch ancestors woulda meant it. Do you know what I mean?” the graying man asked Alice.

She did. The Scots used words like “bogey” and “banshee” for unnamable things with no faces.

“Would you like to hold it?” the graying man offered.

Alice was afeared to touch it. Older items held onto their past like coiled copperheads or a dead wasp that could still poke its barb under your fingernail. Something more than oil and sweat could transfer from a person’s hand onto an object: whatever had been done to exert man’s dominion through that object could jolt through her like a conductor.

“I do,” Alice consented, and reached out to touch it.

And wished she hadn’t.

Alice was taken back long ago-- the past was not dead--but not so very far away--the past was not even past--to a wooded holler—to a once upon a time…

…fairy rings circled so fine. Dancing jigs and reels in their prime. Naidads swimming on their backs in mermaid choreography; sylvans rolling over pine cones like roller derby queens; and dryads tiptoeing through the tulips in the meadows.

Every feature of nature—spring, wood, and meadow--lay under the protection of certain fairy folk suited to the habitation by a likeness and sympathy. But the forty-three foot tall tree with darker than grey bark, often mistaken for an oak, standing proud and sturdy on the Ozark plateau surrounded by some of the oldest rocks on the continent that were still potent enough to send off foo lights like bottle rockets, was a blackjack. This tree was favored by the Marlandyads, a fairy tribe wee smaller than a squirrel’s bahookie. Often decked out in nut-brown troosers and holly green vests, small they were, but mighty when provoked. Their manky magicks sizzled; their hummin’ illusions brought nausea; and their screwball justice twisted like an arboreal constrictor.

These Marlandyads maintained the blackjack by rustling the leaves and shaking the dew off of spider webs. They coaxed sap from the trunk to run down the grooves trapping black soldier ants into prisons of amber. They chased squirrels from the topmost branches and barked at them in bullish tones. They looked after field birds’ eggs, directing leaf-eating grubs into the tufted nests to feed their hatchlings. They flicked beetles off leaf and branch. They rocked their fairy babies away until the bough broke and down they fell, baby, fairy, cradle, and all. They stopped up the front of hornets’ nests to blow smoke through the back to drowse the flying insects before pulling off their wings. And they took great pleasure in shooing away magpies and blue jays.

The Marlandyads redressed wrongs against the tree and the humbuggery of six legged pests and were punitive to the egress and regress of bugbears in leaving their spoor on or near the tree. But there was one pest that could harm both tree and fairy. This one pest was out of the fairy’s jurisdiction and hard, but not impossible, for them to best. This beast was the two-legged, hot blooded, small brained humans.

The first humans who came into the Ozarks were hunter-gatherers and being the same color as the earth, showed respect to the land, the forest, and the creatures. They trekked down paths and followed animal trails. Their villages and habitation never molested the peace of the forest.

Despite fairy cakes left out in the rain with sweet green leafy icing melting as bribes, the fairy folk like to pull all manner of tricks on the earth-toned people: stealing stockings, snapping arrows, and dumping pots of stew into fires of the earth covered humans.

Then came a paler sort of human who weren’t so easy to fluster. First, they came as scouts; then as trappers; and then as squatters. The paths became wagon trails became pea graveled roads became asphalted county roads became highways made of rebar and wire mesh. Camps and fire pits became cabins and hearths became fifteen thousand square foot homes with spreads for work barns, animal mangers, and outbuildings.

These pale two-legged goons had a dominion over anything their hands touched and everything had been put under their feet. They might have been created a little lower than angels, but Ash marked them a sight lower than a goblin. Man had definitely not been created in a fairy’s image.

Where fairy-folk reigned over forest glade and mountain stream, these manky pests had dominion over the fish of the lake and over the fowl in the bush and over the cattle and over every creeping thing that crept the earth—and that was where Ash drew the line: no manky human tube was going to have over a fairy, even a Marlandyad like him.

But these adams had fruited and multiplied so that they not only had replenished the earth—they had overran it—and subdued it—by pollution and toxication—until every living thing that moved upon the earth in either a zoo or a frying pan or the extinction list.

How Ash hated humans.

One by one, the fairy tribes withered away like dried out locust shells. Until only the Marlandyads were left and then they wasted away to one fairy: tiny little Ash and one tree: the blackjack. Ash himself had become allergic to plastic monofilaments which gave him great nosebleeds, but another burgeoning fear was becoming painfully apparent: the sap in his beloved blackjack was running low and more and more leaves turned brown all the more earlier until this last spring not a leaf had turned green at all.

The blackjack had not a single bud and Ash had not a single hope.

The tree was marooned alone in some manky human’s backyard bordered by an asphalt road along one corner and an adjacent wooded lot behind. Landscaped rocks and bushes framed a one story fifteen hundred square foot habitation upon whose roof Ash tossed squirrels in the middle of the night to pester the homeowner. Then claustrophobia set in when a second adjacent wooded lot had been cleared by a gang of humans with backhoes and chain saws only to erect another home with an even steeper roof blocking Ash’s sightlines to the night stars.

It made Ash bilious all the more.

Ash thought he would face the morn’s morn the same as always: protecting a beloved tree now dying with magicks that were now fading, but what Ash saw when he woke one blazing dog day of summer morn made him grow cauld from head to toe.

A man approached the blackjack with a large chain saw. The man had on gloves and goggles: he meant business. The chain was well-oiled and minging, ready to be cranked.

In a dash, Ash was in the air cooing like a doo to lull the man with the saw into thinking he might be a hummingbird rather than a fairy. As Ash flew around the goon, he lit on the chain of the saw and vomited precious pixie dust that would have appeared as glitter to the human upon further instruction. The other paid it never-no-mind, priming the gas on the saw and then cranking it. The spark plug caught, the motor turned, but when the gummified chain links hit the motor, the chain caught and the motor froze and the coils overheated and blowing the sparkplug.

The man with the ruined chainsaw demanded payment before quitting the job.

Not to be out done, the homeowner next contracted a backhoe. It was delivered by a flatbed trailer and dropped off at the front of the yard. The new contractor moved it into position next to the blackjack as Ash’s fairy heart went into tachycardia. The sun had sunk below the tree line, so the contractor parked the backhoe next to the blackjack, turned it off, and took the keys with him promising the homeowner would return in the morn and knock that tree down like a bowling pin.

But Ash knew what he could do to foul up the job.

This would be as easy as eating a fairy cake.

At full dark, Ash slunk off the tree and slipped inside the cab of the backhoe. He didn’t need a key to start the engine, just a little of his precious pixie dust. Fiddling with the manual sticks and power switches—nudging the rumbling backhoe here and guiding the arm there and dropping the bucket to where it shouldn’t go--Ash became a chancer one last time.

That night, Ash dreamed of better times. When the fairy-folk had still been a hardy lot. Smaller than a pine cone. Quicker than a chipmunk. Lovers of savory nuts and roots. Eating their weight in root, leaf, and bark. Taking on all comers and sending the goons running with tails tucked over the gonads.

But Ash woke to a squandered inheritance and a tree bare of leaves and boughs shorn of buds and bereft of animal and insect. The sun was up and both the homeowner and the contractor were at the ready standing next to the backhoe. Ash couldn’t help but giggle as the contractor climbed into the cab and turned on the engine.

The backhoe jerked and did everything that the contractor didn’t want it to do. It fought him at every turn and zigged at every zag. The backhoe turned from the tree and the bucket dug its teeth under a large bolder near the trunk and the contractor could not get a single control to respond. He had no choice but to switch off the engine and toss every toggle and flip every switch.

When the contractor restarted the engine, he had dominion again.

Except for the bucket.

It was hooked under the large boulder and every move of the crane brought the backhoe close to tipping over. The contractor jockeyed the backhoe this way and that way, but the bucket would not let go. It clutched one of the oldest rocks on the continent like a precious stone and would not let go. The contractor scooted the backhoe up against the bucket which pinched the angle of the arm. The bucket groaned and its teeth scraped against the boulder like raking steel fingernails, but the boulder was released and the machine shuddered as its full weight fell back on the treads.

The contractor turned off the backhoe to survey the machine for damage. It bore red Ozark clay and white scratches, but, worst of all, the top of the bucket was cracked. Ignoring the imploring of the homeowner to finish what had been started, the contractor swore off the job, but not before demanding payment in full.

After tangling twice with humans and their machines, Ash had come out on top.

Ash felt as good as in the days of auld when any pest—be they two- or four-footed—would be stone cauld crazy to come up against any one of the Marlandyads. Ash felt his juices flowing like sap oozing out from under the bark. He laughed so hard he had to grab the sole of his booted foot. Then he showed the human homeowner something he could not have dominion over: Ash dropped his troosers and shook a few bars of the bare butt boogie.

But Ash still hadn’t learned the golden rule of pests: they didn’t give up until the pestered gave in. And with the king of pests, humans, there was a platinum rule: since they held dominion over all the earth, humans had the upper hand—they wouldn’t quit until a mountain was a pile of rubble at their feet.

Ash could grant that the homeowner had an axe to grind, but never in a million cracked nuts would the fairy think the homeowner would grasp for such a tried and true method. Chopping down something to size with the elimination of an object by force through means of a frictive wedge with a sharp edge.

The homeowner called in a third person to remove the tree.

This man was as a tall as a young dogwood and as thin. There were sunglasses over his eyes and a kerchief across his mouth and something long in his hand.

An axe.

The man stood six feet tall and the handle was at least four feet long.

Ash was taken with the wonderment of the axe’s workmanship. With its balanced head and flanged cheeks and well polished bit and teeth. The man held it by the belly and cradled its throat.

But if the man thought he would succeed where saw and backhoe failed, he had another thing coming. Sure the blade might scrape some bark off, but it would take years of swinging to cut down Ash’s precious blackjack.

The tall man swung the axe. It swam against the bark. Cut through the wood. Split fiber and shore off dust.

Ash felt every minging blow from his little fairy head to his big toe. The hurt throbbed as the tree screamed in his ear.

The man pulled out a wedge of heart wood.

Ash was crushed.

Then the man put on spiked shoes and a harness. He knew his business. He had done this before.

The man climbed the trunk and almost standing perpendicular, he cut into the tree. Bit to bark. Cheek to heart-wood. Heel to wood-grain. Toe to sawdust. Chopping, slicing, the axe sung its song. Verse after verse by the psalter blade.

The man climbed to different heights and repeated each blow, measure for measure. It was his inheritance. His preeminence and dominion.

After delivering such repeated blows, the man climbed back down and swung again against the base where he had taken out a wedge.

The wedge became a gash became a rift became a channel became a sundering unto the wood grain until the tree became shaky, wobbly and all shoogly. It teetered; it tottered. It fought gravity and lost. It came crashing down and splintered in a huge crash of bark and sawdust.

A tree fell in the woods and there was a noise and there were two persons there to hear it: the feller and the fairy.

Both were dumbfounded.

The feller, soaked in sweat, was covered in sawdust and splinters thought he saw a flash of blue light, a crackle and a pop and a snap. It pulsed and was gone.

The fairy gave up his thick barked ghost, but not without a curse. “Never again will your ax cut down a home. Never again will you mark a trunk with your stroke. Dull will the blade be.”

The feller heard the words like a rumble against his ears. He didn’t want to believe it until he looked at the ax blade. It was chipped and roughed, never to cut again.

Man might have dominion, but that didn’t mean lesser creatures couldn’t give him a hard time now and then and not get in a lick of their own: one last gesture out of spite for spite’s sake to stab at a human from the mouth of hell.

It would have to satisfy the fairy because death wouldn’t.

“Sad story,” Alice said. “For the fairy.”

“Sadder still for the axe,” the man said and name a price not for its damaged value of function, but for its place in the story of man’s dominion.

(photo credit: Jeffrey Cummins)

How lovely to meet another faith and fiction writer! I enjoyed this little tale, you have a way with words

@S.L. Stallings, thank you for the like!